Google manipulated ad auctions and inflated costs to increase revenue, harming advertisers, the Department of Justice argued last week in the U.S. vs. Google antitrust trial.

What follows is a summary and some slides from the DOJ’s closing deck, specific to search advertising, that back up the DOJ’s argument.

Google’s monopoly power

This was defined by the DOJ as “the power to control prices or exclude competition.” Also, monopolists don’t have to consider rivals’ ad prices, which testimony and internal documents showed Google does not.

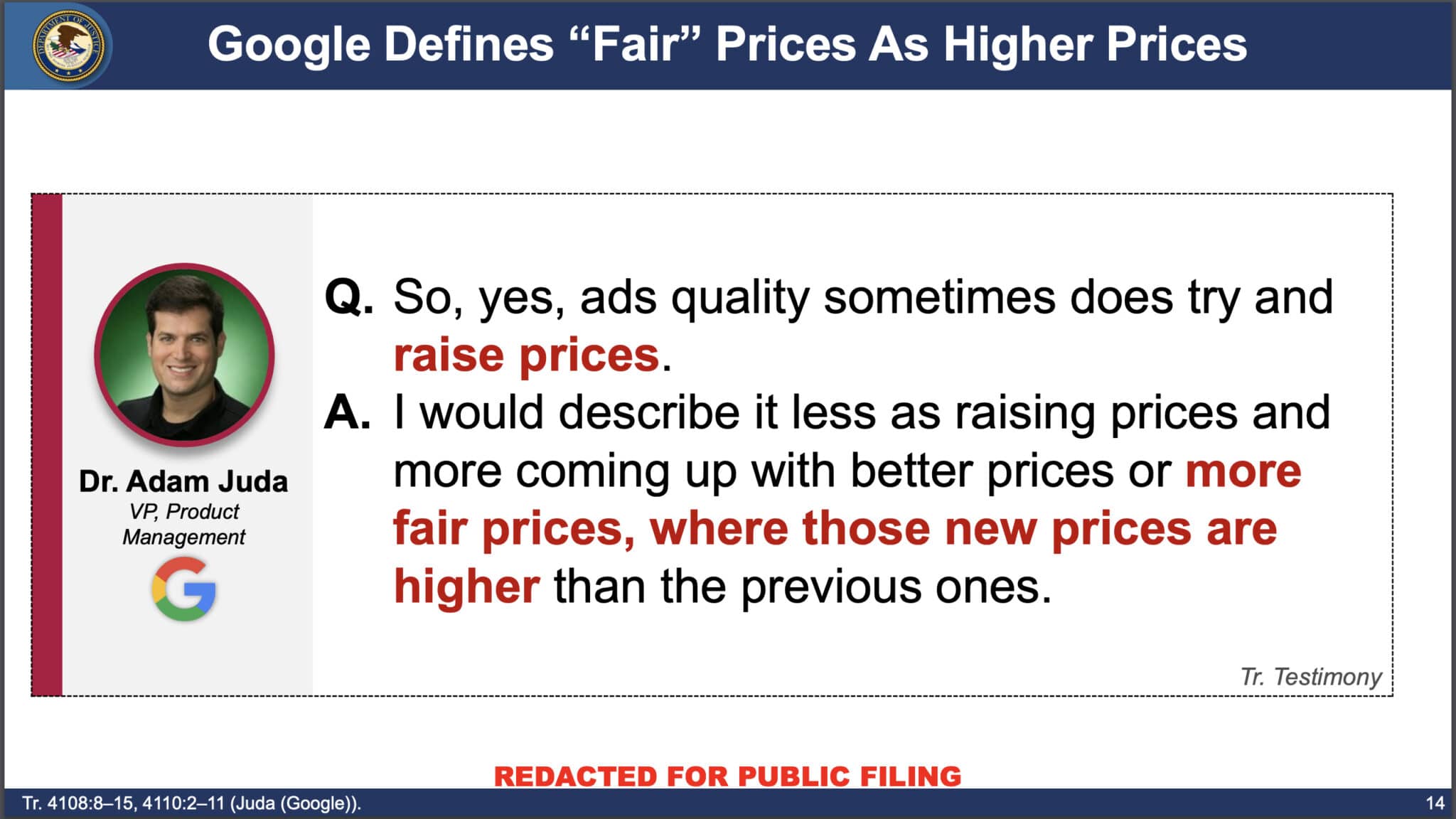

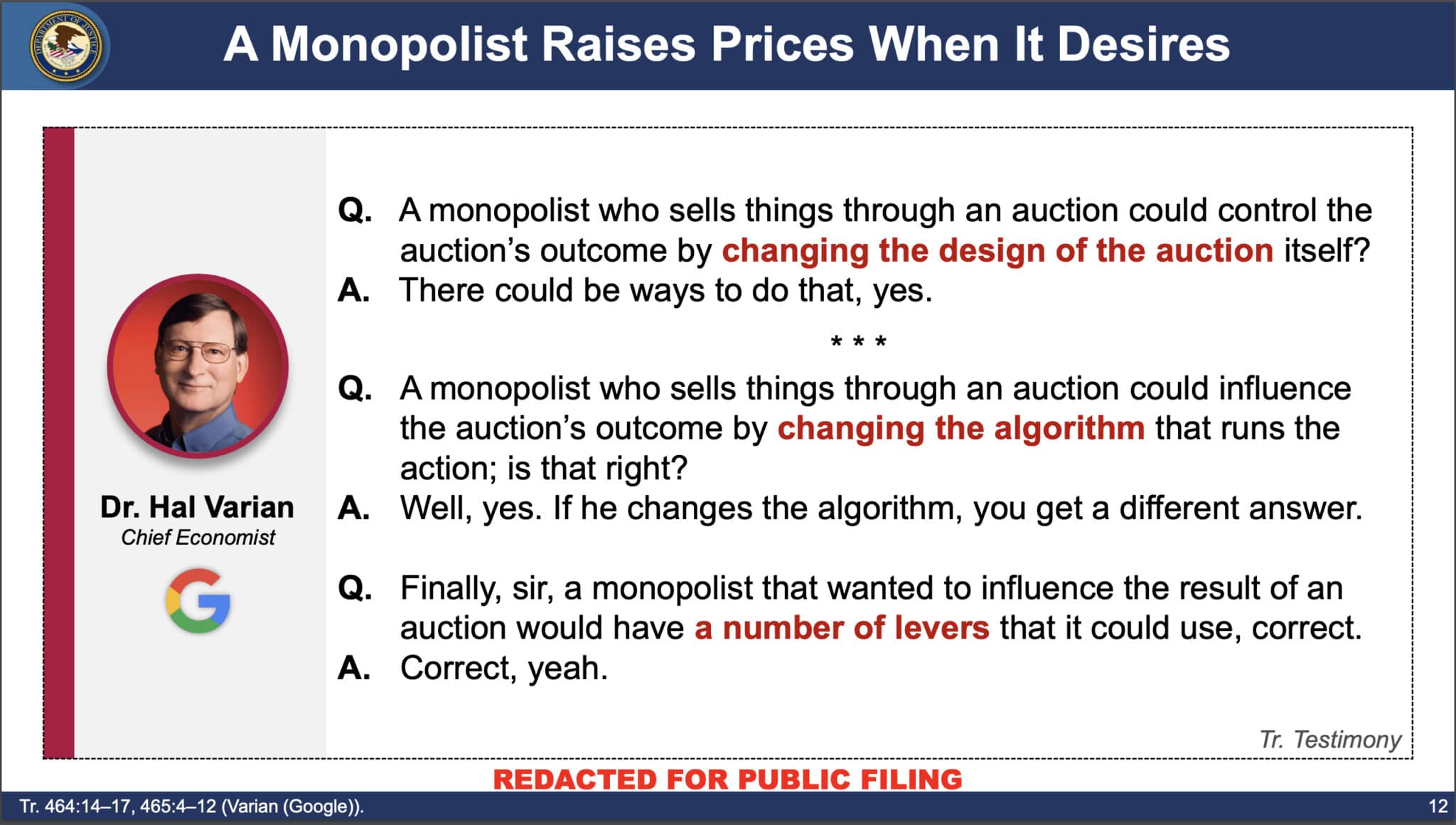

To make the case, the DOJ showed quotes from various Googlers discussing raising ad prices to increase the company’s revenue.

- Dr. Adam Juda said Google tried to come up with “better prices or more fair prices, where those new prices are higher than the previous ones.”

- Dr. Hal Varian indicated that Google had many levers it could use to change the ad auction design to achieve its desired outcome.

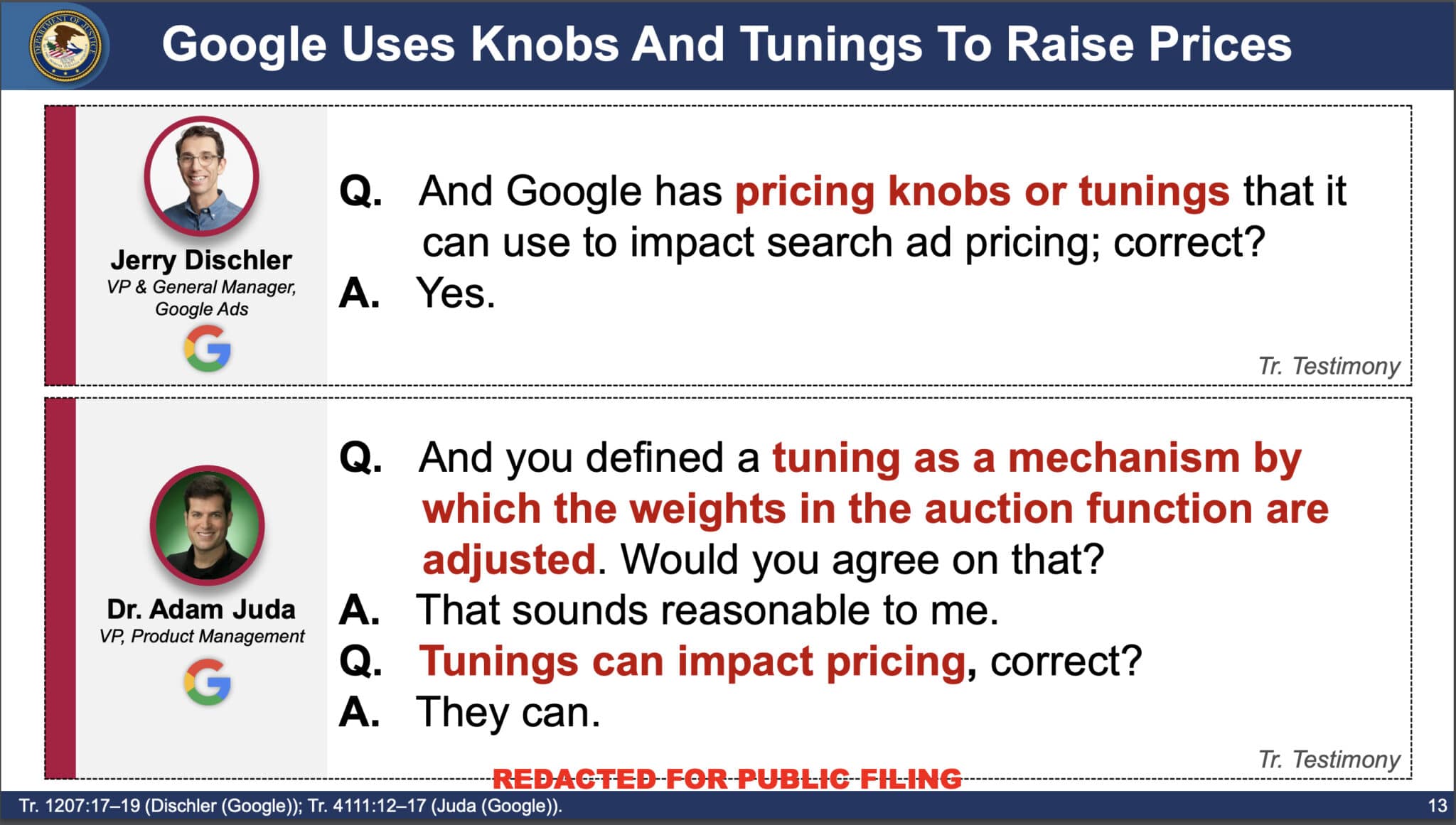

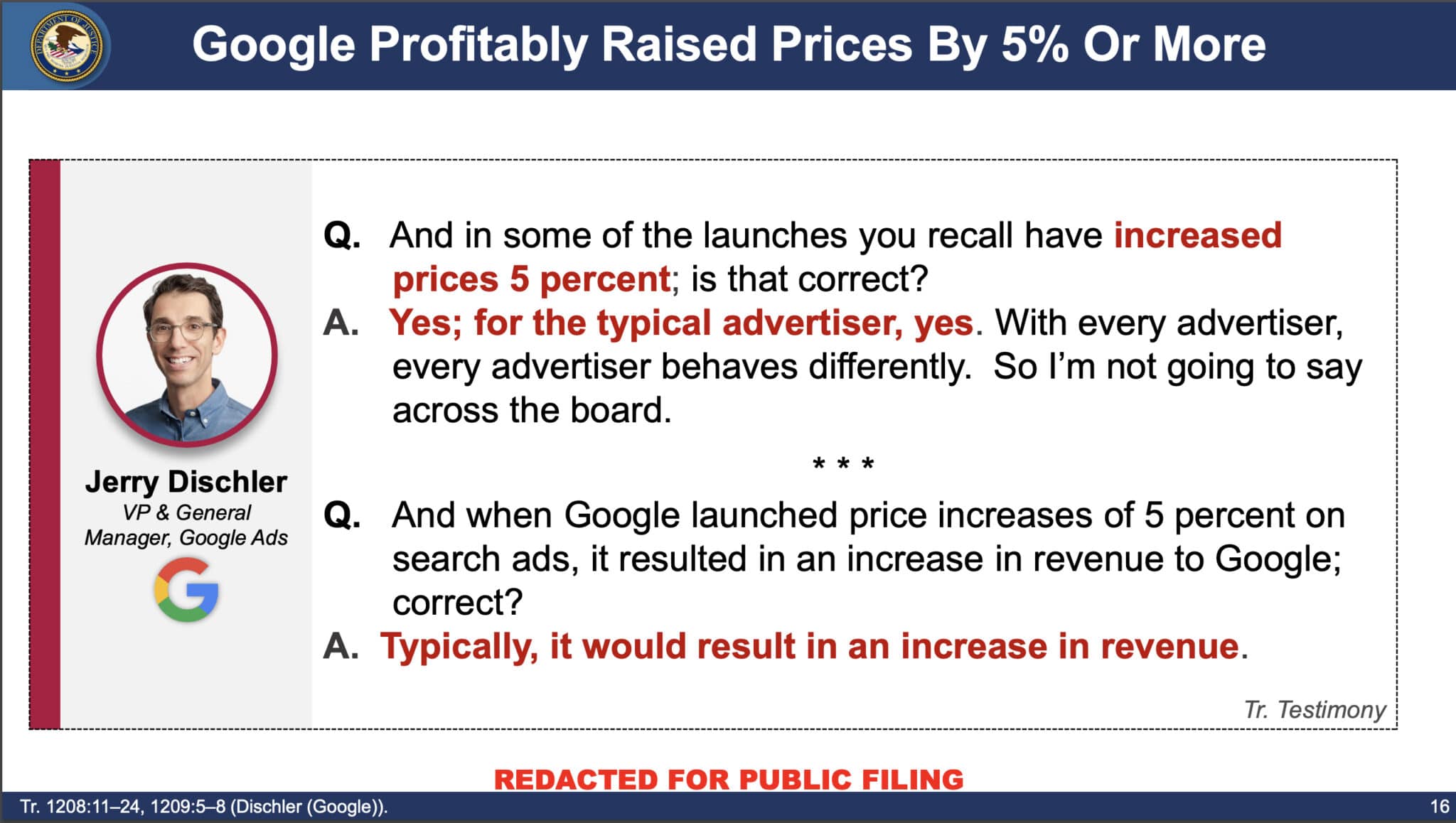

- Juda and Jerry Dischler confirmed this. Dischler was quoted discussing the impact of increasing prices from 5% to 15% in these two slides:

Other slides from the deck the DOJ used to make its case:

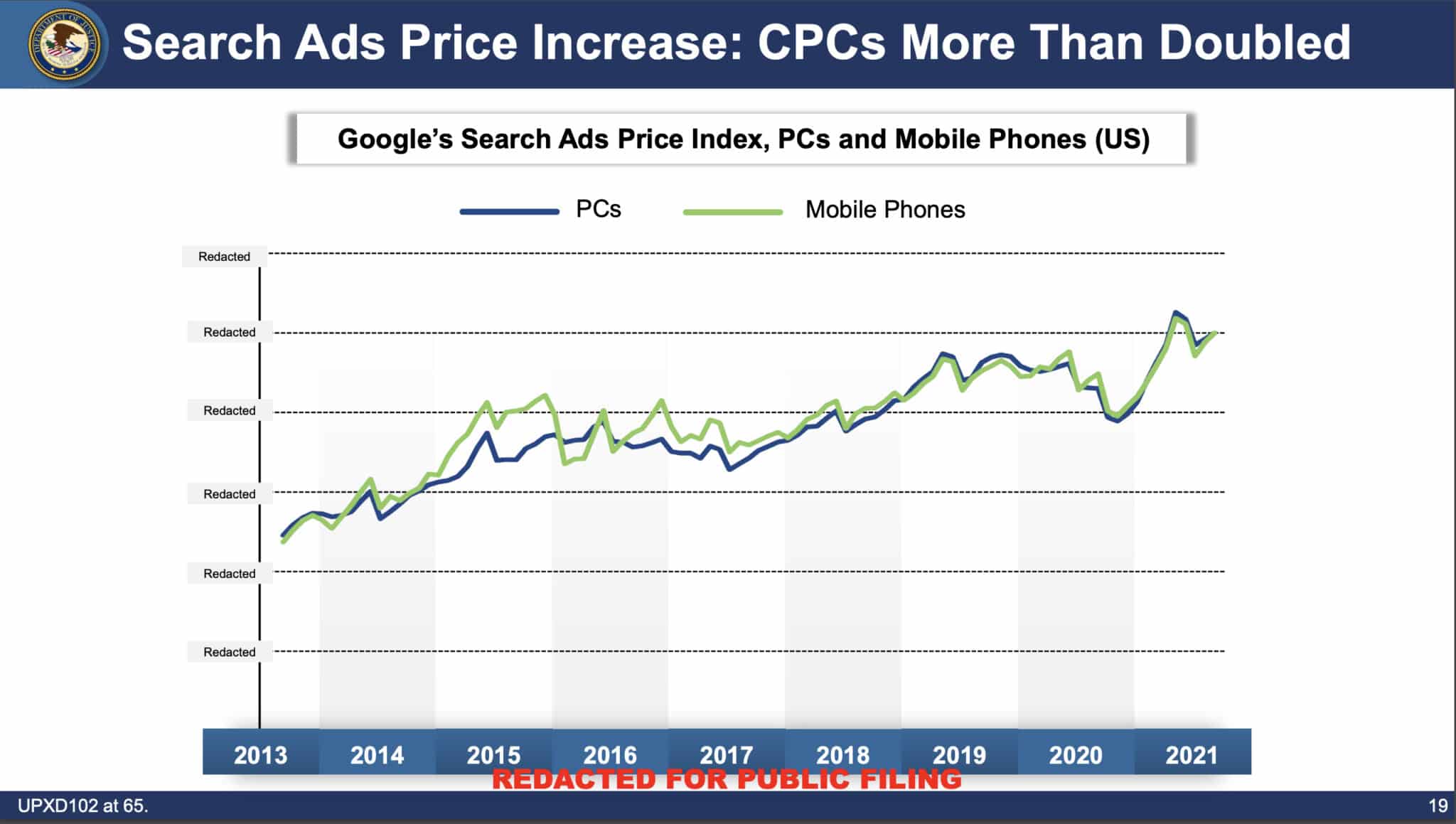

- Google Search ad CPCs more than doubled between 2013 and 2020.

Advertiser harm

Google has the power to raise prices when it desires to do so, according to the DOJ. Google called this “tuning” in internal documents. The DOJ called it “manipulating.”

Format pricing, squashing and RGSP are three things harming advertisers, according to the DOJ:

Format pricing

- “Advertisers never pay more than their maximum bid,” according to Google.

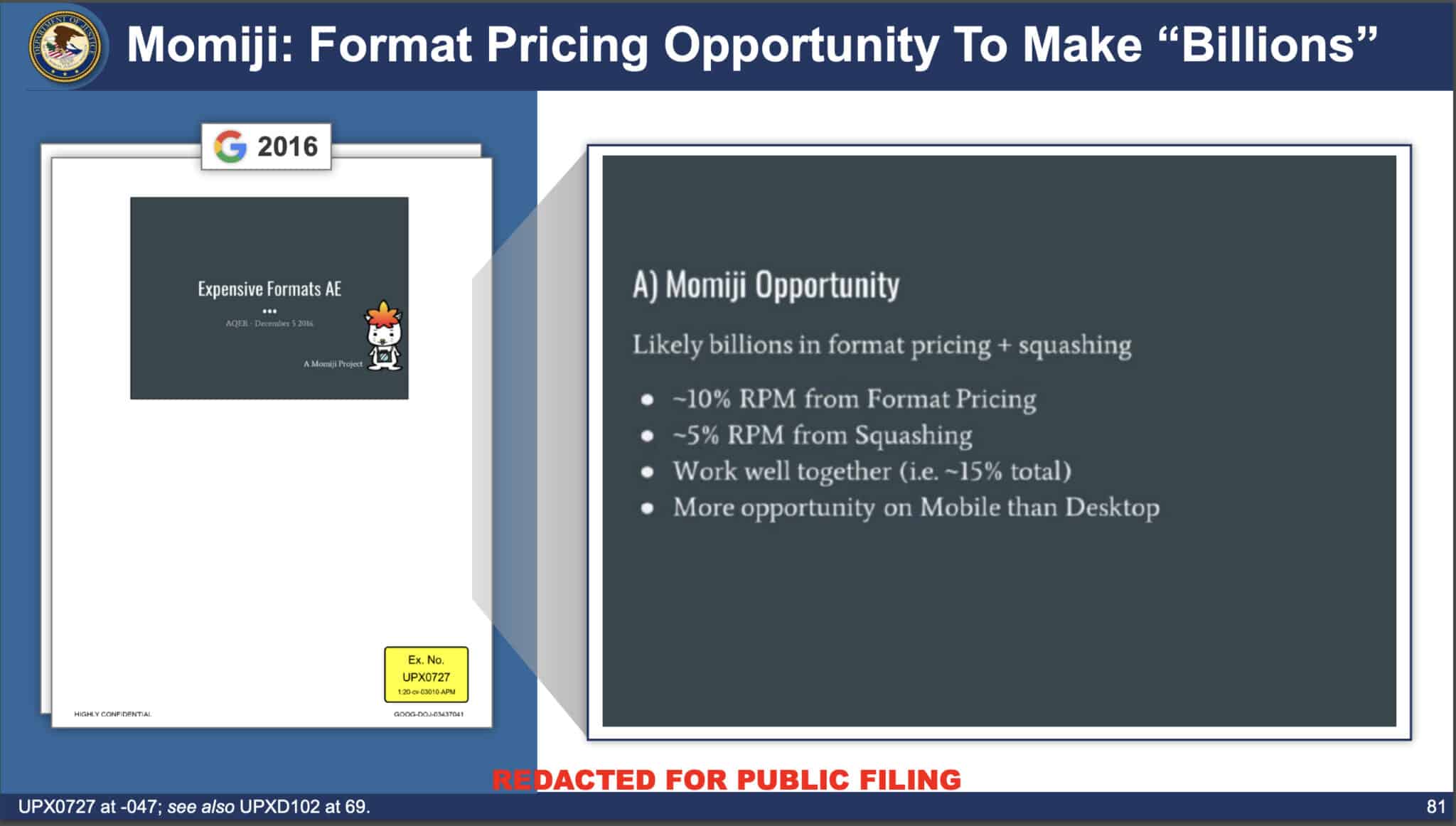

- Yes, but: What Google failed to mention is “Project Momiji,” which very quietly launched in 2017.

- What is Momiji: It artificially inflated the bid made by the runner-up.

- The result: A 15% increase for the “winning” advertiser. More ad revenue for Google.

- Relevant slides: From the DOJ’s deck:

Squashing

- How it worked: Google increased an advertiser’s lifetime value based on how far their predicted click-through rate (pCTR) was from the highest pCTR. According to a 2017 document introducing a new product called “Kumamon,” Google had been doing this using “a simple algorithm consisting of bid, three quality signals, and some (mostly) hand tuned parameters.” (A screenshot of this document seemed to indicate Kumamon would add more machine learning signals in the auction.)

- In other words: Google raised “the price against the highest bidder.”

- Google’s goal: To create a “more broad price increase.”

- The result: The Google ad auction winner paid more than it should have if squashing wasn’t part of the ad auction.

- And: The DOJ indicated this all led to a “negative user experience” as Google ranked ads “sub-optimally in exchange for more revenue.”

- Relevant slides: From the DOJ’s deck:

RGSP

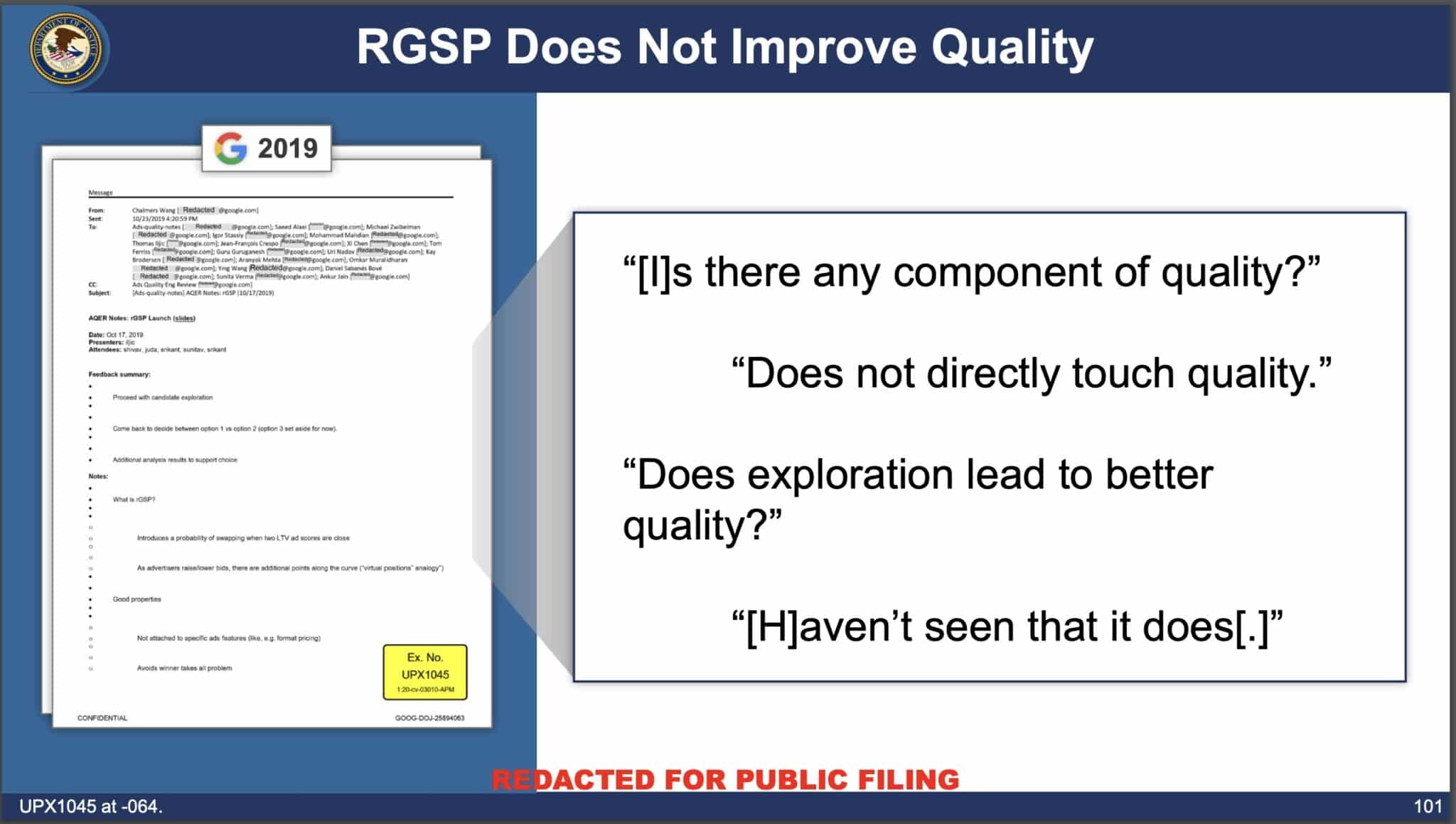

- What is it: The Randomized Generalized Second-Price was introduced in 2019. (Dig deeper. What is RGSP? Google’s Randomized Generalized Second-Price ad auctions explained)

- How it worked: Google referred to it as the ability to “raise prices (shift the curve upwards or make it steeper at the higher end) in small increments over time (AKA ‘inflation’). It did not lead to better quality, according to 2019 Google emails.

- How Google talked about it: “A better pricing knob than format pricing.”

- The result: It incentivized advertisers to bid higher. Google increased revenue by 10%.

- Relevant slides: From the DOJ’s deck:

Search Query Reports

The lack of query visibility also harms advertisers, according to the DOJ. Google makes it nearly impossible for search marketers to “identify poor-matching queries” using negative keywords.

The DOJ’s presentation. You can view all 143 slides from the DOJ: Closing Deck: Search Advertising: U.S. and Plaintiff States v. Google LLC (PDF)

from Search Engine Land https://ift.tt/x8FeU0G

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment